Vehicular tailpipe emissions around the world keep getting tighter. But the US is taking a different approach compared to Europe and China.

Major cities across the world have enjoyed cleaner air and clear, blue skies during some months of the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic. The current global crisis is certainly not an ideal way to get those results, but it begs the question: can we preserve our fundamental right to clean air without sacrificing economic growth? Anti-pollution measures being adopted by major nations across the world give hope that it is indeed possible.

It is easy for us who live in the United States to take clean air for granted. It is important to remember, however, that it has occurred progressively through decades of regulatory actions and technological advances. This year marks the 50th anniversary of the U.S. Clean Air Act, and it is apt that we reflect on and celebrate the progress in reducing air pollution that has been made over these past several decades, while also considering the possibilities ahead.

For much of the world’s highly populated regions, air pollution is a real concern and is taking its toll on human health. In its annual “State of Global Air 2020”, the Health Effects Institute points out that 90% of the world’s population is still exposed to much higher concentrations of PM2.5 (particles smaller than 2.5 microns, known to cause a host of cardiovascular health issues) than the World Health Organization’s recommended 10 mcg/m3. Air pollution was linked with 6.67 million deaths globally in 2019, far higher than the 1.3 million deaths associated with traffic collisions.

There are various sources of air pollution, but the transportation sector has gained much attention as a key contributor to ambient concentrations of particulates and nitrogen oxides (NOx), and this is rooted in both history and modern-day environmental statistics.

How the US tackled air pollution so effectively

Let’s look at the history. Back in 1970, sweeping new federal regulations required clean-air compliance from every segment of industry as the US grappled with poor air quality in its urban centers. After the formation of the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), the Clean Air Act of 1970 was promulgated and established air-quality standards to strictly limited levels of six pollutants that threatened public health: carbon monoxide (CO), nitrogen dioxide, particulate matter, sulfur dioxide, hydrocarbons, and ozone. Automakers had to design vehicles that could run on unleaded gasoline and incorporate a new device – the catalytic converter – to significantly reduce pollutants from car exhaust.

The results achieved since the passing of the Clean Air Act are astounding. Even though the US economy has grown fourfold since the 1970s, ambient air pollution has dropped more than 70%. Reduced vehicular emissions were a key contributor, driven largely by the application of the catalytic converter. Compared to the 1970s, tailpipe emissions of CO, NOx and particulates today have reduced by over 95%, the equivalent of taking millions of cars off the road!

The impact on ambient air quality here in the US has been noticeable as a result, with concentration of PM2.5 decreasing nationwide by 43% since 2000. The Clean Air Act has served as a model and blueprint for emissions regulations around the world, resulting in significant emissions reductions from passenger cars globally.

Europe and China are leading boldly to reduce particulate emissions

Today, however, the US is no longer setting the latest, tightest standards across all emissions categories. In recent years, Europe and China have taken bolder steps in emissions regulations by setting a limit not only for the mass of particles emitted from vehicles, but also on the number of soot particles allowed in vehicle exhaust as a means of reducing the emissions of ultra-fine particulates.

These regulations, specific to gasoline vehicles, address the elevated particulate emissions from modern, fuel efficient, gasoline-direct-injection (GDI) vehicles. The limits in these new European and Chinese regulations require automakers to add gasoline particulate filters (GPFs) to their emissions control systems. These highly efficient exhaust filters prevent most of a vehicle’s ultra-fine particulates (those smaller than 100 nanometers in size) from leaving its tailpipe and entering the atmosphere. In light of the ongoing pandemic, it is worth highlighting emerging evidence which suggests that COVID-19 particles are transmitted through adsorption on ultra-fine particles which are 100 nm or smaller, and which can linger in the air for a long time.[1]

Europe also instituted real-world driving emissions norms to ensure that the emissions standards are met not only in laboratory tests, but are also compliant in a wide range of on-road driving conditions that simulate how people drive every day.

It is unfortunate that while new car models sold in Europe and China will be equipped with GPFs, the same will be sold in the US without one. Hopefully future regulatory tightening in the US will help address this gap. If not, this is a lost opportunity for immediate progress as gasoline vehicles make up most of the fleet in the US, and every other vehicle sold today is a GDI. Ultra-fine particles emitted by these vehicles are endangering our health, but health issues may be mitigated with these filters that are already commercially available in Europe and China.

Moreover, recent studies have demonstrated that there is no “safe” lower limit of particulate concentration for human health, pointing to the need to continued reductions of emissions limits.[2]

Other advances in the coming years to ensure further emissions reductions

Advanced engine technologies and after-treatment systems with all the latest particulate and cold-start technologies have resulted in near-zero – and in some cases even “negative” - emitting vehicles, meaning tailpipe concentrations can sometimes be even lower than ambient concentration of air pollutants. In fact, several studies suggest that in the coming years, particulates generated from brakes and tire wear will likely exceed those emitted from tailpipes equipped with filters.[3]

While the catalytic converter remains a modern marvel by converting over 99% of harmful NOx and other pollutants once the exhaust gas heats up the catalyst, there is still room for improvement. During the first one to two minutes after engine ignition, the catalyst temperature is still low, leading to high emissions. Technologies are being developed to reduce these “cold-start” emissions, allowing the catalyst to reach operating temperatures even faster and reducing the last major source of vehicle emissions occurring in urban centers.

Further steps are taken to ensure vehicle’s compliance with emissions regulations. Regulators are implementing tighter in-use emissions control through on-board diagnostics, monitoring of NOx and fuel consumption and real-time transmission of this data through telematics. Major cities across the world are considering leveraging remote sensing to identify high-emitting vehicles and implementing geofencing on plug-in hybrid vehicles to ensure the vehicle switches to electric-only mode when entering a city’s reduced-emissions zone.

We have certainly come a long way since the smog-filled days of Los Angeles in the 1970s. As we celebrate the 50th anniversary of the U.S. Clean Air Act, we are approaching a new era where tailpipe emissions are testing the instrumentation limits of detection and showing the possibility of negative emitting vehicles. But it is questionable if we can further improve our air quality without governmental support. New regulations in the spirit of the Clean Air Act are the main way to ensure that the United States continues its clean-air progress in the coming years by leveraging the newest automotive emissions technologies available.

_______________________________

[1] TIME. “COVID-19 Is Transmitted Through Aerosols. We Have Enough Evidence, Now It Is Time to Act”. Accessed November 9, 2020. https://time.com/5883081/covid-19-transmitted-aerosols/

[2] Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health. “Evaluating the impact of long-term exposure to fine particulate matter on mortality among the elderly”. https://advances.sciencemag.org/content/advances/6/29/eaba5692.full.pdf

[3] Air Quality Expert Group. “Non-Exhaust Emissions from Road Traffic”. https://uk-air.defra.gov.uk/assets/documents/reports/cat09/1907101151_20190709_Non_Exhaust_Emissions_typeset_Final.pdf

Substrates and filters have done tremendous work in making the air around the world cleaner. How do these technologies work?

"The limits in these new European and Chinese regulations require automakers to add gasoline particulate filters (GPFs) to their emissions control systems. These highly efficient exhaust filters prevent most of a vehicle’s ultra-fine particulates (those smaller than 100 nanometers in size) from leaving its tailpipe and entering the atmosphere."

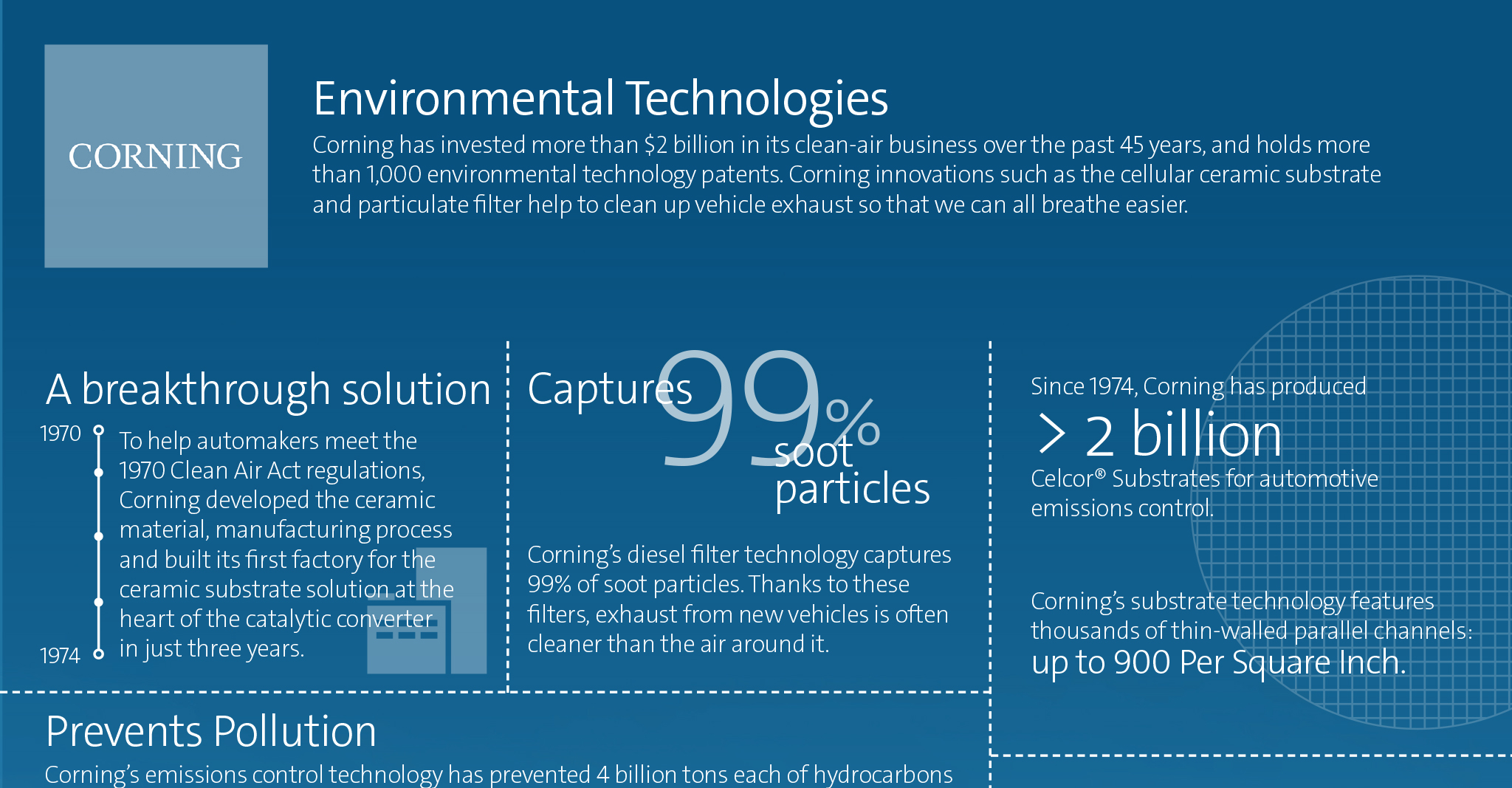

Corning has invested more than $2 billion in its clean-air business over the last 45 years. This infographic summarizes some of the key facts around our emissions control innovations.