Creative collisions are helping forge new frontiers in glass technology

Right brain or left brain? Emotion or logic? Artist or scientist?

In a world that loves the simplicity of binaries, it’s tempting to view art and science as opposites. Popular culture helps perpetuate that notion, from stereotypes of artists and scientists on sitcoms to Facebook quizzes that place people into tidy categories. But I was able to do my part to help dispel that myth recently, when I was asked to deliver a keynote speech as part of the Art + Science series at the Rockwell Museum, a Smithsonian Affiliate in Corning, New York. And it’s an ongoing theme in my work.

My roles at Corning Incorporated and the Corning Museum of Glass give me a unique seat at the intersection of high technology and art. Moreover, the material at the center of my work—glass—embodies the marriage of the two, with its remarkable combination of technical and aesthetic properties.

Despite our tendency to place them on opposite ends of the spectrum, art and science share many key ingredients. For example, they both involve acts of creation; innovations in both fields often stir up controversy; and practitioners of each go through similar development processes, including building on the knowledge that came before them and undergoing iterations before producing a satisfactory result. But I find the synergies even more interesting than the similarities.

Collisions Between Artists and Scientists

In the book Where Good Ideas Come From, popular-science writer Steven Johnson used the term “collisions” to describe the experience of perspectives from different fields of expertise converging in a shared physical or intellectual space. I love that term and am a firm believer in the notion that ideas and the state of the art evolve faster when diverse perspectives collide and interact frequently.

Johnson shared an anecdote about how the molecular biologist and neuroscientist Francis Crick conceived of the complementary replication system of DNA by thinking of how a sculpture can be reproduced by making an impression in plaster and later using that impression as a mold to create copies. That example of art inspiring science motivated me to look for examples of how science has inspired art. Thanks to my work at the Corning Museum of Glass, I didn’t have to look far. Karen LaMonte, whom I know from her beautiful glass sculptures of dresses, recently worked with a team of climate scientists at Caltech to sculpt a 7-foot-tall, 2-and-a-half-ton marble cloud that captured a real cloud’s actual weight and mass.

While my personal experiences are not as groundbreaking as Crick’s or as breathtaking as LaMonte’s, collisions have impacted my own life and work. For example, when I joined Corning in 2011 and was looking for a home in the area, I brought a contractor friend along to inspect a house I was considering. My friend remarked that the house’s glass walls created an amazing energy. Although he was probably unaware of it, he was echoing a sentiment from the renowned architect Le Corbusier, who once called glass “the most miraculous means of restoring the law of the sun.”

I ended up buying that house and can confirm my contractor’s and Le Corbusier’s observations. But this experience was also valuable to my work. It supported Corning’s investment in a company called View, which is developing electrochromic windows that can transition from transparent to opaque on demand. The technology eliminates the need for shades and makes it possible to experience the benefits of natural light. How significant are those benefits? A recently completed Cornell study showed that electrochromic windows in an office reduced eye strain by 51%, headaches by 63%, and drowsiness by 56%, while increasing overall productivity.

The Marriage of Form and Function

Not surprisingly, art and science are colliding more than ever in Corning’s products. We invented Corning® Gorilla® Glass, for example, to meet a customer’s desire to produce a smartphone that featured both beauty and durability. From an aesthetic point of view, consumers want sleek designs. But from a technical point of view, they need a glass that resists damage from drops and scrapes.

Corning® Fibrance® Light-Diffusing Fiber is an example of a product that took Corning’s expertise in fiber-optic technology and turned it upside down – or more accurately, inside out—to create a compelling mix of technical and aesthetic properties. With conventional fiber optics, the objective is to keep the light inside – hence the term “low-loss” optical fiber. But Corning designed Fibrance to emit light along its length. It can be used for a variety of design applications– e.g., to illuminate shadowy areas like stairwells, to make sports equipment and clothing visible at night, or simply to add color and ambiance to an environment.

Corning is also developing products that help automakers raise the bar for style as well as performance. The thin form factor, light weight, superior optics and multi-touch responsiveness of Gorilla Glass make it possible to create car interiors featuring elegant dashboards, curved consoles, and multi-directional displays with the sophisticated capabilities consumers have come to expect from their smartphones.

Ultimately, we’re trying to create that perfect marriage of form and function. We want to unleash new capabilities and solve tough problems, but we also want to develop products that create powerful emotional connections by combining elegance with technical sophistication.

Proactively Creating Collisions

We understand that collisions between artists and scientists can help us achieve that, so we are proactively creating such opportunities. One of the best examples is Corning’s Artist-in-Residence Program.

Launched five years ago, the program grew out of the close collaboration between Corning’s glass scientists and the technical curators of glass art at the Corning Museum of Glass. We invite world-renowned glass artists to spend time at our Sullivan Park research and development campus in Corning, New York, where they work with glass chemists and engineers and use technical glasses to create new art. The program stimulates artists to reimagine their process and their artwork, and it helps scientists to think more artistically and creatively about their own projects.

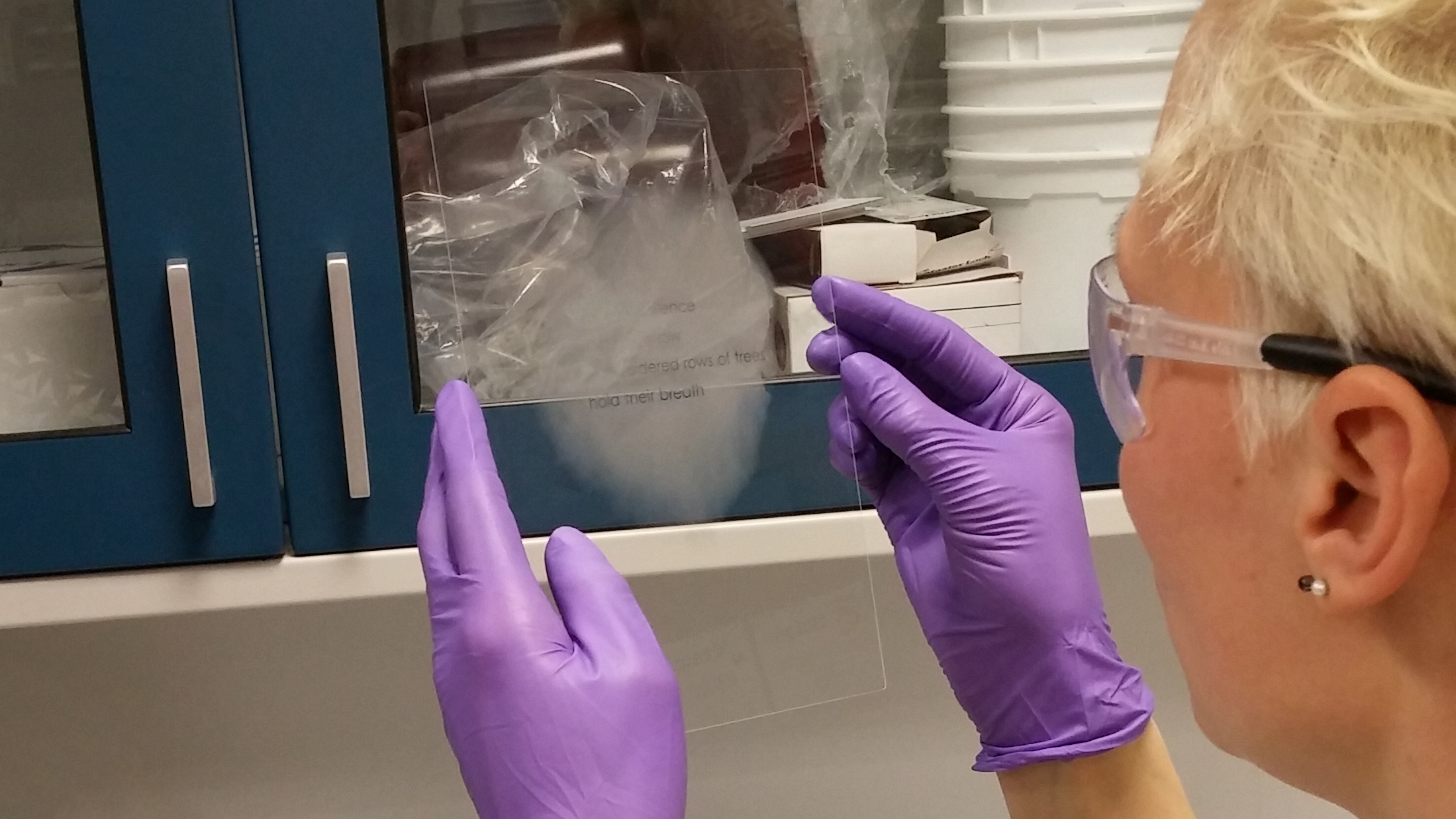

Anna Mlasowsky is one of the glass artists who participated in the program. She wanted to create a “Book of Breath”: a book of clear glass sheets, where the print would only become visible when someone breathes on it -- similar to the way you can write, and later read the writing, on a steamed-up window or mirror.

Bringing the project to life required several specialized Corning technologies: glass science, knowledge of polymers, experience in thin films and surfaces, vapor deposition, and specialized techniques for printing on glass. Michelle Wallen, a distinguished associate in Corning’s Glass Research division, was one of the host scientists working with Mlasowsky and admits to being skeptical because the project was so complicated. She told me she “jumped through the ceiling” when it worked.

Although Corning doesn’t have any plans to commercialize the unusual printing capability, the project expanded our scientists’ knowledge and tool set, as much as the artist’s. As one of the few companies that remain committed to exploratory research, Corning firmly believes that focused investments to extend knowledge in our core areas of expertise are always worthwhile.